How to clean up space debris

By Dominic Bliss

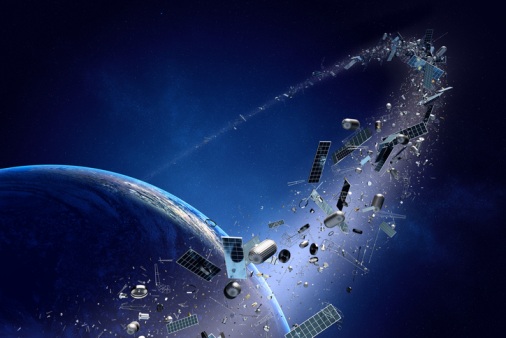

Millions of pieces of debris from defunct satellites and spacecraft litter the Earth’s orbit. Disaster looms if we don't start cleaning it up. But how?

A collision between two satellites in Earth’s orbit is virtually unknown. But it can happen.

On February 10th, 2009, 490 miles above Northern Siberia, it did happen. Two satellites smashed into each other at thousands of miles an hour, instantly shattering into smithereens. One was a 560-kg operational communications satellite called Iridium 33, the other a 900-kg defunct Russian satellite called Kosmos 2251. The accident created a debris field of thousands of pieces of space junk. Although, at the time, there were fears for the safety of the International Space Station, fortunately they proved unfounded.

Since the Russians launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first space satellite in 1957, around 9,600 of these devices have entered Earth’s orbit. According to the European Space Agency’s space debris office (in Darmstadt, Germany), there are currently around 5,500 satellites still circling our planet, 2,300 or so of them actually functional. The problem is they’re not built to last forever, and occasionally they break up due to disintegration, explosions or, in the case of Iridium 33 and Kosmos 2251, head-on collisions. Right now it’s estimated that, circling the Earth, there are 34,000 pieces of space debris larger than 10cm in diameter; 900,000 pieces measuring between a centimetre and 10cm; and a staggering 128 million pieces smaller than a centimetre.

While most of this debris derives from defunct satellites, there are also fragmented, derelict rocket bodies and sections of spacecraft. According to the European Space Agency, since the dawn of the space age, there have been around 500 “break-ups, explosions, collisions, or anomalous events resulting in fragmentation”.

All that debris swirling around our planet obviously poses serious risks to other satellites, to the International Space Station, and to any future space missions. It’s a mess up there. Very occasionally, debris too large to burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere will even fall down to Earth.

Fortunately, there are space companies now specialising in space debris removal. One of them is Astroscale. Headquartered in Tokyo, and with offices in the USA, Singapore, Israel and the UK, they plan to offer a commercial service in removing junk from Earth’s orbit.

Harriet Brettle is head of business analysis at Astroscale’s UK office in Harwell, in Oxfordshire. She explains just how urgently the space industry needs to clean up its act: “Even something the size of a 10-pence coin can cause catastrophic damage to a satellite, due to the speeds at which objects are travelling round the Earth,” she told Chart. “We see quite a lot of satellite explosions and fragmentations where a satellite has been left in orbit at the end of its operational life. Due to the space environment it’s exposed to, things break off, parts explode and you get a proliferation of those small pieces of debris. That's what we’re really worried about because they can still cause damage, yet they are so small we can’t track them.”

Space debris orbiting at lower levels in Earth’s orbit naturally burns up when it is pulled low enough into the atmosphere, drawn down by forces such as atmospheric drag, lunar perturbations, perturbations in Earth’s gravity, solar wind and solar radiation pressure. But debris at very high altitudes could remain in orbit for millennia.

Astroscale are currently at the testing stage of debris removal. Their first major mission will take place in early 2023. Working with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), they will launch a satellite (called ADRAS-J) which, if all goes to plan, will approach close to an upper-stage Japanese rocket body spinning in Earth’s orbit, in order to assess it for future removal. The second stage of the mission (which has yet to be agreed) would be to use an Astroscale spacecraft to drag the rocket body into the Earth’s atmosphere, where it would burn up.

Such a spacecraft has yet to be built. But, as Brettle explains, it would probably weigh a few hundred kilogrammes and would use robotic arms to connect with the rocket body. “Our spacecraft will have on-board propulsion,” she says. “Once we’re physically connected to the rocket, we take over manoeuvrability, and then adjust our position and altitude to bring it down to a lower altitude where it burns it up.”

In the future, it’s hoped that all satellites launched from Earth will be fitted with docking plates so that they can be easily retrieved once they reach the end of their working lives. In late 2020 Astroscale plan to demonstrate how this technology might work when they launch two spacecraft stacked together.

Once in orbit, using a magnetic docking mechanism, the two craft will repeatedly separate and dock before eventually de-orbiting and burning up on re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere. The mission is called ELSA-d.

There are very few occasions when space debris has been retrieved in the past. One famous example was back in 1984, during a Space Shuttle Discovery mission, when NASA astronaut Dale Gardner and his crew retrieved two satellites (Palapa B-2 and Westar VI) which had accidentally been placed in improper orbits, and safely returned them to Earth.

But this involved human astronauts. Brettle claims Astroscale’s ELSA-d mission will be the first example of autonomous debris removal. “The first end-to-end debris removal demonstration where we identify, rendezvous, capture and de-orbit an object,” is how she describes it.

The issue of space debris is further complicated since, in space, there are few recognised international regulations; only guidelines and standards. “Wild West is definitely a phrase that has been used before,” Brettle says of this lack of regulation. “There are no internationally agreed rules of the road when it comes to space traffic management. As we launch more and more satellites into space, we still lack that international consensus. Where is your satellite going? What happens if it comes close to someone else’s? What happens if your satellite fails? How do we protect the environment from future debris?

This explains why the work of Astroscale and similar space companies is so vital. Already Astroscale has worked with the European Space Agency and JAXA. In the future they hope to collaborate with other space agencies.

Founded and led by Japanese entrepreneur Nobu Okada, the company currently has 130 employees worldwide, and growing. Eventually, Brettle hopes, they will be viewed as a vital emergency service that comes to the aid of other space companies when their satellites break down.

“I see Astroscale becoming the AA of space.”

Authored by MS Amlin

About MS Amlin

MS Amlin is a leading global specialty commercial insurer and reinsurer with operations in the Lloyd’s, UK, Continental European and Bermudian markets.

Comprising Mitsui Sumitomo’s London and Bermuda-based operations and the historic Amlin businesses, MS Amlin specialises in providing insurance cover for a wide range of risks to commercial enterprises and reinsurance protection to other insurers around the world.

It is wholly owned and fully supported by the financial strength and scale of MS&AD of Japan, the eighth largest non-life insurer in the world. To learn more, visit www.msamlin.com.